Every word you write in a legal brief can tip the scales. Your credibility with the judge, opposing counsel, and clients depends on how clearly you present your case. Persuasive writing isn't about flowery language or clever turns of phrase—it's about precision, structure, and clarity. Learning how to write a clear and compelling legal argument is a skill that separates lawyers who win cases from those who leave judges confused.

In the legal profession, your brief is your voice in court. When you can't speak directly to the judge, your written work must do the talking. That means every sentence, every citation, and every transition matters. Clear and persuasive writing shapes how the court understands complex legal issues, evaluates your credibility, and ultimately rules on your case. Persuasive arguments don't emerge from dense paragraphs of legalese—they come from organized thoughts, plain language, and a deep understanding of what your audience needs to hear.

This guide walks you through the core elements of effective legal writing. You'll learn how to structure a statement of facts, cite relevant legal authority, use persuasive language without sacrificing clarity, and refine your drafting through careful editing. These aren't abstract principles—they're practical tips that lawyers across every practice area can apply immediately to strengthen their legal documents and serve their clients better.

Understanding the Legal Context and the Role of a Legal Brief

A legal brief is your written argument to the court. Its purpose is to convince the judge to rule in your favor. Your brief defines what the case is really about and why the court should care. Effective brief writing demands precision, clarity, and strategy so you can frame the controversy, set the stakes, and give judges a concrete path to ruling for your client.

Judges prefer concise briefs with limited presentations of arguments. Brief, clear essays are the most persuasive parts of briefs. Your job is to make the judge's work easier by presenting a clear, reasoned path to your desired outcome. When you understand the legal context—the specific practice area, the applicable law, and the procedural posture—you can organize relevant facts and legal authority in a way that builds credibility from the first page.

A strong brief frames the dispute through multiple lenses. You need a narrative lens that covers who the parties are, when and where the dispute arose, and why your client is in the right. You need a logical lens that lists three or four specific points you would make to a judge who gave you just 60 seconds to explain what you want and why you should get it. You need a pragmatic lens that gives the court a reason to feel good about ruling in your favor. And you need a contrasting lens that draws a line in the sand between the two competing views of your dispute.

The standard structure of a brief includes a table of contents, table of authorities, statement of facts, argument section, and conclusion. Each section should be clearly labeled and organized logically. Headings matter—they should be complete sentences making positive points, not neutral topic labels. Point headings serve both organizational and persuasive functions by defining the structure of arguments and inviting readers to draw conclusions.

Structuring Your Statement of Facts for Maximum Impact

Your statement of facts is where you establish the foundation for every legal argument that follows. A strong statement of facts provides context, influences how the court views the case, and sets the stage for a good argument. According to Georgetown Law's writing guidelines, the statement of facts is a critical segment of an appellate brief that should be written persuasively while remaining accurate.

Lead with a narrative line that shows how the parties reached an impasse. Craft active-voice headings for the statement of facts, perhaps in the present tense. This approach keeps the reader engaged and makes the facts feel immediate and relevant. When the plaintiff filed the case, what specific legal issues arose? What key facts support your position? Present these details in chronological order so the reader can understand the context without getting lost in a jumble of dates and events.

Almost every sentence in your statement of facts should be followed by a citation to the specific page of the factual record. This isn't just a technical requirement—it builds credibility. When you cite relevant facts with precision, you show the court that your narrative is grounded in the record, not in wishful thinking. But don't let citations overwhelm the story. Use active voice to maintain clarity and a persuasive tone. Instead of writing "The contract was breached by the defendant," write "The defendant breached the contract."

Well-organized sentences create a more effective writing flow. Break up longer sentences into shorter, punchier ones. Use transitions to guide the reader from one point to the next. When you need to illustrate a complex point, include an example that makes the concept concrete. For instance, if you're explaining how a regulation applies, show how it played out in a specific scenario from your case.

You also need to handle unfavorable facts with care. Rarely does every fact favor the prevailing party. To maintain credibility, nod to bad facts and then neutralize them by controlling how they appear in context. One strategy is to embed unfavorable facts in "Although" clauses and then turn the reader's attention elsewhere. This approach concedes the core fact but minimizes its length, importance, and visibility.

Leveraging Relevant Legal Authority and Persuasive Authorities

Citing relevant legal authority is what transforms your narrative into a legal argument. But many lawyers mishandle authority by treating cases as ends in themselves rather than tools to prove a point. When you use an authority as an end in itself, you force your reader to supply the missing logical links while wading through irrelevant facts and language. The result: the reader feels more confused than ever and skips to the next paragraph.

The fix is simple. When it's time to discuss a case or order, use your own words first to explain how the authority proves the point you're making today. Only then should you summarize facts or copy any relevant language. Your argument, not case law, should control your structure. Each of your points should flow logically to the next, with each paragraph beginning by stating what the law is rather than how it developed.

Distinguish between mandatory authority and persuasive arguments. Mandatory authority—statutes, regulations, and binding precedent from your jurisdiction—carries the most weight. Persuasive authorities, such as decisions from other jurisdictions or secondary sources like treatises and law review articles, can support your position when mandatory authority is sparse or ambiguous. But don't overload your brief with persuasive authorities. Select the strongest examples and explain why they should guide the court's decision.

Remind the court of the purpose behind legal doctrines. Judges appreciate when lawyers connect the dots between abstract legal principles and practical outcomes. If you're arguing that a particular statute should be interpreted broadly, explain why that interpretation serves the statute's underlying goals. Enumerate points within the argument so that the role of each authority in the chain of reasoning is explicit. This approach makes your brief easier to follow and harder to refute.

Using Persuasive Language and Plain Language to Communicate Clearly

Persuasive language and plain language aren't opposites—they work together to create clear and persuasive writing. Judges, opposing counsel, and clients are all inundated with information and have limited time. The trend in legal writing is unmistakably moving towards simplicity and clarity. The days of lengthy, jargon-filled legal documents are fading, with courts and clients now favoring clear, concise language.

Strong legal writing starts with clarity and conciseness. Break up longer sentences, use shorter words, and maintain tight prose throughout. Favor short words like "can" and "but" over longer alternatives. Use transitions such as "In so doing" to take the reader on a smoother ride. Vary your sentence structure and shake loose from repetitive patterns like "Someone noted that…" or "The court observed that…"

Active voice is preferred in legal writing because the sentence construction is usually more concise and who is doing what will be more clear. There are specific situations where passive voice can enhance flow, but those are exceptions. Most of the time, active voice keeps your writing direct and forceful.

Avoid bad writing pitfalls by simplifying legal terms when possible. You don't need to eliminate every piece of legal terminology—terms like "plaintiff," "defendant," "mandamus," and "mens rea" are legitimate terms of art. But you should avoid archaic phrases like "hereinafter aforesaid" or "whereof" that add no meaning and make your brief harder to read. The movement toward plain English began in the 1970s to make legal documents more accessible to the public, and it has commercial benefits including reduced costs and increased profits for businesses.

Focus on language clarity to ensure the reader understands the main argument. Balance brevity and depth to keep legal documents concise yet effective. Your goal is to make the reader like you, see you as helpful, and trust you. This is crucial because readers—judges or opposing counsel—hold either the power to decide critical issues or control compensation for your clients' harms.

Developing Legal Writing Skills through Practice and Feedback

Legal writing skills improve through continuous practice, peer review, and reflection. No lawyer emerges from law school as a polished writer. It takes years of drafting, revising, and learning from mistakes to develop a persuasive writing style that wins cases and builds credibility across the legal industry.

Schedule regular reviews of your written work to ensure clarity and structure. After you finish a draft, set it aside for a day or two if time permits. When you return to it, you'll spot weaknesses you missed the first time. Read your brief aloud. If a sentence sounds awkward or confusing when spoken, it will read the same way on the page.

The editing process is where good briefs become great. Editing uncovers mistakes or weaknesses in your arguments that you overlooked while drafting. It's also where you tighten your prose, eliminate redundancy, and sharpen your transitions. Many briefs suffer from choppy and repetitive transitions, with too many sentences that start with a transition word followed by a comma, and then string together abstract clauses that are long on nouns and short on verbs. The solution is to add a new transition word or phrase to your repertoire regularly and consult resources that offer lists of transition words to make your logic clear.

Obtain valuable insights from mentors, colleagues, or resources like BriefCatch. Peer review and feedback from colleagues can significantly enhance the quality of legal writing. When someone else reads your brief, they bring fresh eyes and can spot ambiguities or logical gaps that you missed. They can also tell you whether your argument is as persuasive as you think it is.

The more often you use tools and techniques that reinforce good writing habits, the less you need them. The suggestions become second nature. This improves your overall writing and saves time. Each edit delivers authoritative content and gives context for every suggestion, reinforcing skills with every draft. Over time, you'll internalize the principles of clear and persuasive writing, and your first drafts will be stronger than they used to be.

Drafting Contracts and Other Legal Documents with Concise Arguments

Drafting contracts and other legal documents demands the same clarity, persuasive structure, and consistent language that you bring to a legal brief. Contracts may not be arguments in the traditional sense, but they still require compelling arguments about what the parties intend, what obligations they accept, and what remedies apply if something goes wrong.

Balance formal legal terms with plain language for the audience. Contract drafting should emphasize clear, concise, and understandable language. Ensure sentences are no more than two lines long, use headings and subheadings for organization, and employ active voice instead of passive for directness. Maintain consistent terminology throughout the document so that the same concept is always described with the same words.

Ensure each point in the document flows logically to enhance readability. A contract should tell a story: what the parties are agreeing to, when and how they will perform, and what happens if they don't. Use descriptive headings and subheadings to guide readers through the document. This makes it easier for clients to understand what they're signing and for courts to interpret the contract if a dispute arises.

Why cohesive arguments across sections maintain effective communication? Because contracts are often read in pieces, not from start to finish. A client might jump to the termination clause or the indemnification section without reading the entire document. If each section is self-contained and clearly written, the reader can understand it in isolation. But if sections contradict each other or use inconsistent language, confusion and disputes follow.

Integrate relevant legal authority for credibility and clarity. Even in a contract, you may need to reference statutes, regulations, or case law that govern the parties' obligations. For example, if you're drafting a non-compete agreement, you might cite the applicable law that defines what restrictions are enforceable in your jurisdiction. This shows clients that the contract is grounded in legal reality and helps opposing counsel understand the legal context if they review the document.

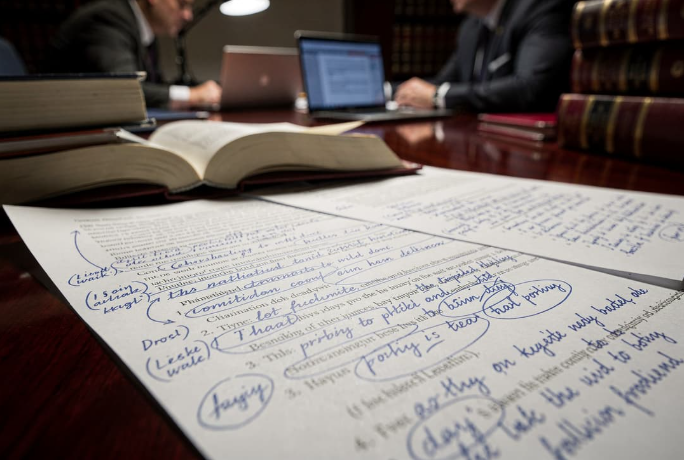

Avoiding Bad Writing through Careful Sentences and Detailed Editing

The editing process is where you refine each brief and address bad writing issues. Errors in grammar, spelling, and punctuation can undermine the credibility of your writing and create confusion for the reader. Misplaced commas or incorrect punctuation can change sentence meaning and lead to significant ambiguity in legal contexts.

Correct ambiguous sentences and reorganize key points. If a sentence can be read two different ways, rewrite it so there's only one possible interpretation. If your argument jumps around, reorder the paragraphs so each point builds on the one before it. Maintain credibility in the court by removing unnecessary words. Every word should earn its place on the page. If you can cut a word without changing the meaning, cut it.

Why rewriting certain document sections can highlight the applicable law? Sometimes a section is technically accurate but still confusing because it buries the key legal principle under layers of detail. When you rewrite, lead with the legal rule, then explain how it applies to your facts. This makes it easier for the judge to follow your reasoning and see why you should win.

Double-check citations, grammar, and structure for consistent persuasive legal writing. Citation errors undermine credibility. Common mistakes include failure to italicize case names, improper abbreviations, incorrect statute citations, and missing pinpoint citations. Basic rules matter too: periods and commas go inside closing quotation marks, and you capitalize "Plaintiff" and "Defendant" only when referring to the parties in your case, not in general discussion.

Use a methodical approach to comma placement rather than relying on intuition. A comma guide can help you avoid the "I-feel-like-there-should-be-a-pause-here method" and instead apply clear rules on introductory clauses, non-restrictive elements, conjunctions joining independent clauses, and the Oxford comma. Similarly, avoid comma splices—when two independent clauses are joined together with a comma without a coordinating conjunction or other appropriate punctuation mark. The fixes are simple: use a period, use a coordinating conjunction, use a semicolon, or use a colon when the second clause illustrates or explains the first.

Lasting Impact: Elevating Your Legal Writing to Win Cases and Serve Clients

Every word matters when submitting a brief to the court. It's the difference between winning and losing a case. The stakes are high when trying to persuade the court in your favor. High-quality legal writing positively affects case outcomes by enhancing the persuasiveness and accuracy of arguments. Well-written documents improve judges' comprehension of case merits, increasing the likelihood of favorable rulings.

Judges respond positively to clear legal writing. As Hon. William D. Stein of the California Court of Appeal puts it: "If you can't write, you can't win." Chief Justice John Roberts emphasizes that your brief writing conveys a sense of your credibility and the care with which you put together your case. When writing is unclear, it becomes a confession of incompetence.

Continuous practice and clear and persuasive writing build credibility in the legal field. The more you write, the better you get. The more feedback you seek, the faster you improve. The more you study examples of excellent legal writing—from Supreme Court opinions to briefs by top advocates—the more you internalize the techniques that make arguments compelling.

A well-structured legal brief matters in any legal context. It doesn't matter if you're drafting a motion to dismiss, an appellate brief, a contract, or a client memo. The same principles apply: clarity, conciseness, logical structure, and persuasive language. When you master these principles, you serve your clients better, you win more cases, and you build a reputation as a lawyer who knows how to communicate effectively.

Use tools like BriefCatch for constant growth in legal writing skills. BriefCatch transforms Microsoft Word into an intelligent editing environment purpose-built for lawyers, offering tailored edits for briefs, memos, and client work. It delivers AI-powered Bluebook corrections, expert writing suggestions, and seamless editing. The platform analyzes legal documents with over 11,000 editorial recommendations, helping you maintain firm-wide writing consistency through scoring dashboards.

Embrace consistent revisions and advanced writing strategies to improve every brief. The editing process should focus on clarity, coherence, and logical flow of arguments. Revising legal documents often requires multiple rounds to tighten arguments and improve clarity. But each round makes your brief stronger, your argument more persuasive, and your credibility more solid. In the legal profession, the person who writes clearly and persuasively has a distinct advantage. Make that person you.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)